New Research Shows East Portland is Hot Spot for Canopy Loss

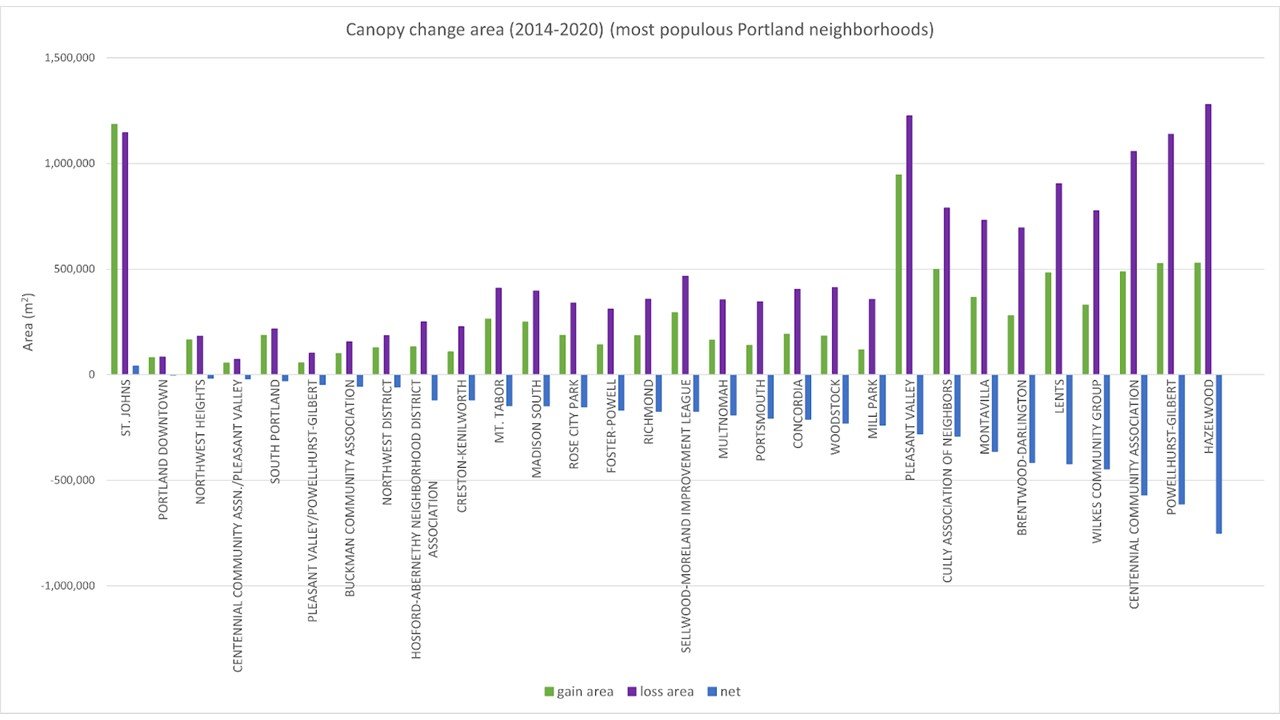

Graphic from Vivek Shandas

Aerial images of Portland taken from 2014 to 2020 indicate that neighborhoods east of highway 205 have experienced the greatest percentage of canopy loss, according to PSU Professor Vivek Shandas, who presented his preliminary research findings on December 14, 2021, at an OMSI Science Pub talk. The neighborhoods with the most canopy loss are Hazelwood (which may have lost more than 3,100 large-form trees during this time period), Powell-Gilhurst, Centennial, and Lents. St. Johns’ gains and losses evened out. [Article continues below graphic.]

Grapic credit Vivek Shandas

Grapic credit Vivek Shandas

Professor Shandas specializes in urban forestry and tree equity, and developing strategies for reducing impacts from climate change. By using high-resolution aerial images to describe the extent of canopy loss, Shandas’s research team is shedding light on neighborhood-level green space changes that are often undetectable. What he and co-presenter Aaron Ramirez, assistant professor of biology and environmental sciences at Reed College, found is that the areas with greatest canopy reduction are also, temperature-wise, the hottest.

What’s causing the tree loss, which is contributing to rising temperatures in these neighborhoods? Shandas’s team is exploring development pressures and weather factors such as extreme heat and drought. Early findings suggest that a combination of housing sales and population growth are major contributors. (Note from Trees for Life Oregon: housing sales in East Portland often lead to new development, which often results in tree loss, though Shandas has only been able to use housing sales data and can’t yet empirically prove the link between tree loss and development.)

Ramirez reported that his Reed colleague, Dr. Hannah Prather, is also finding that some tree species are faring better than others in our hotter summers, and that the site of individual trees affects their adaptation to a changing climate. For instance, at the end of 2019 Douglas-firs showed some resistance to high temperatures when growing in warm sites, while Western redcedars showed reduced resistance when in hot sites. As foresters have observed for several years, some of this species has been dying region-wide.

In a related study sponsored by the National Science Foundation, Shandas’s team found that Portland’s heat-stressed trees and heat-related human deaths in summer 2021 occurred geographically close to one another. This, said Shandas, is due to decades of urban planning that continues to disinvest in some parts of the region while better preparing other areas for hotter summers. “Values translate to policies, which are then noticeable through studies of physical landscape changes and their related consequences,” he said, referring to the fact that in Portland, as in many U.S. cities, low-income residents often live in low-canopy, highly paved neighborhoods that historically have seen little investment, including in space for trees.

Responding to an audience question about how we should talk about urban infill and the potential loss of green space, Shandas drove home some of the same points that Trees for Life Oregon is making to City leaders: A big part of the solution, he said, lies in the design and standards we use for urban development practices and the extent to which they directly address climate change. “It’s also about soil and space for trees. Portland’s tree code and zoning code play a role, as do City agencies, developers, and individual households.” To find more space for trees, he added, “We need to look at the city as an ecosystem, considering that the land we occupy has been forested for millennia.” For example, we should be considering things like what he calls “transit arboretums,” created by planting trees on bus curbs/islands.

In the spirit of what Trees for Life Oregon also believes is needed, one audience member said he’d like to get his neighbors to agree to a six- to eight-foot right-of-way to accommodate large-form trees “rather than the three-foot strips we have now.” This, he said, will require giving up part of the street and getting City leaders to think bigger picture about how to prepare for a changing climate.

Over the coming years Shandas and his team will continue describing the role that current policies play in amplifying temperatures and accelerating shade inequities. Equally important will be identifying what strategies could enable verdant urban forests in areas facing the greatest canopy losses.