Portland Parks’ Urban Forestry Is Now Using a Nifty Efficiency Tool

A newly adopted web-based system is saving significant staff time, streamlining workflow, and improving intra-office communication.

By Kyna Rubin

In 2025, Portland Parks & Recreation’s Urban Forestry reduced by hundreds of hours the time it takes for staff and contractors to enter data for the thousands of tree inspections and maintenance tasks they conducted. And they cut down from two weeks to two hours how long it takes to map out routes for the summer seasonal staff who water and maintain all newly planted trees in parks and City properties.

They did this, says Jeff Ramsey, Urban Forestry’s science and policy coordinator, with a new time- and money-saving tool that Urban Forestry started adopting in late 2024. TreePlotter is a software platform developed by Colorado-based PlanIT Geo. The online asset management system enables staff to enter, store, and track data from tree inventories, inspections, and work tasks all in one place.

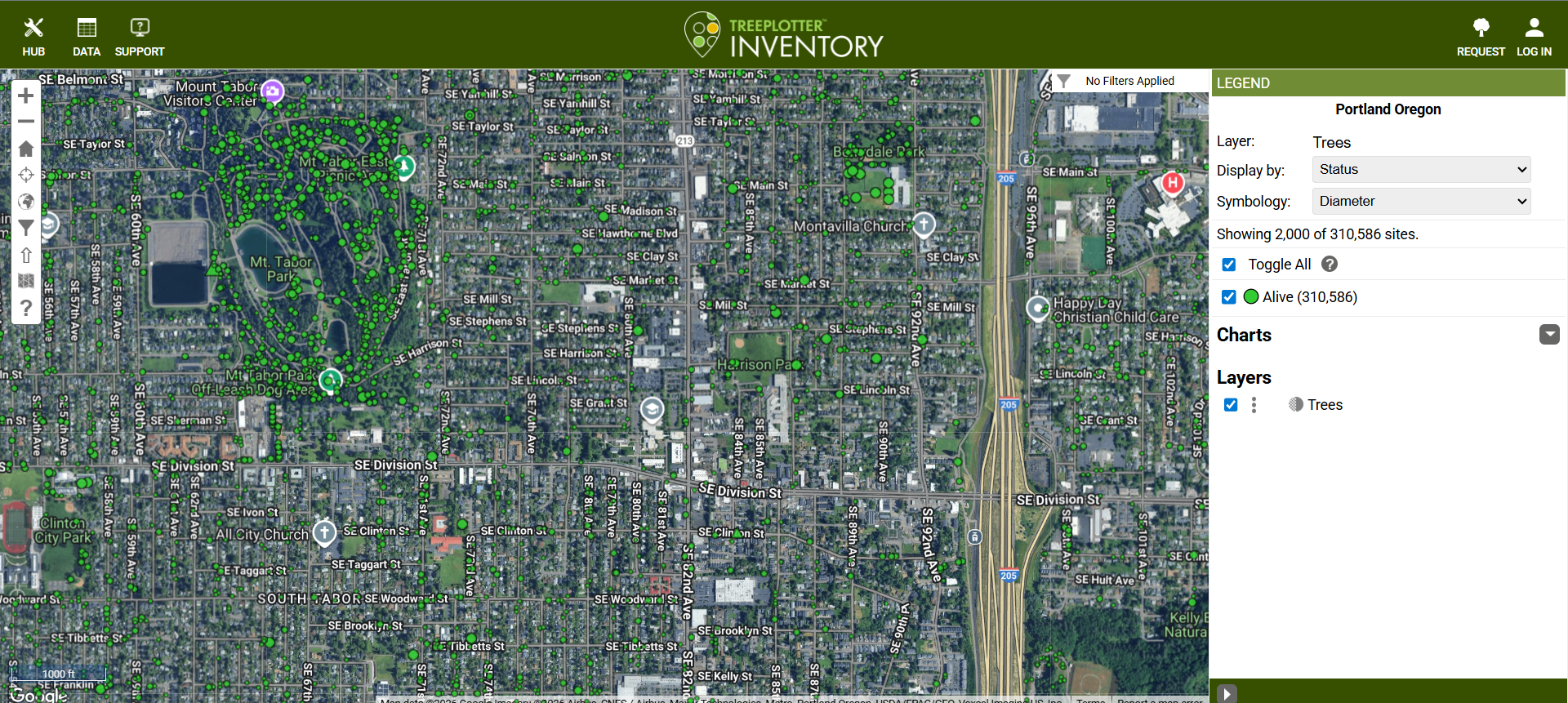

A screenshot of a TreePlotter Inventory interactive map showing trees in Mt. Tabor Park, on the left, and in nearby SE Portland.

This is a big leap. Prior to using TreePlotter, Urban Forestry was storing tree inventory and other data in a few different GIS-based systems that could not interact with one another and were not accessible by everyone in the Parks Bureau. Staff were relying on paper to manage work orders for the City arborists who perform maintenance on some 3,000 to 4,000 park and other City property trees each year. Now, through TreePlotter, all staff can access what different teams are doing via one system.

An Urban Forestry contractor using TreePlotter in the field. Photo by Urban Forestry.

Ratcheting up cross-team communication, says Ramsey, is one of TreePlotter’s best features. Project managers can use it to see what’s happening in the field “in real time,” thereby more quickly and effectively assigning work tasks. The platform stores basic information about tree location, size, species, when it was planted, and by whom. That information can then interact with inputs created by different teams that handle, say, tree inspections or pest and pathogen management.

Now, when inspectors go out they use their phone or tablet to log into TreePlotter, where they can find the tree location and post their findings and photos directly into the system, where all UF teams can see them. Once they note if action is needed, say, to prune a failing branch, they immediately assign that work and due date to a particular staff person who will instantly see that task on their to-do list. Everything entered is uploaded to the cloud.

Some Context

Cities nationwide such as Vancouver, Tacoma, Austin, and Boulder are tracking their work with TreePlotter. In Oregon, Portland is one of some 50 towns and cities that have adopted it, with the help and encouragement of the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF). Eugene has been using it the longest.

“Growing efficiency will boost parks maintenance in the wake of the city’s November 2025 passage of the latest five-year Parks levy.”

Right now, 20 or 30 more communities are interested in tapping it, says Scott Altenhoff, manager of the Oregon Department of Forestry’s Urban & Community Forestry program. ODF set up a contract with TreePlotter Inventory as early as 2015, but municipalities weren’t much interested in using it then and the pandemic further delayed its adoption, he says.

Other, similar canopy-tracking software exists. For instance, The Nature Conservancy has just developed a tree canopy tool, notes Altenhoff. American Forests has one, and the tree company Davey has its Treekeeper platform. But Altenhoff and his colleagues selected TreePlotter because they found it the most user-friendly, comprehensive, and time-tested. TreePlotter was in the vanguard, having created its inventory component about 15 years ago, he says.

Propitious Timing

TreePlotter comes to Portland at a good time. Growing efficiency will boost parks maintenance in the wake of the city’s November 2025 passage of the latest five-year Parks levy. This tax provides the funds for Parks to continue the expanded work it started in 2021 with support from the previous Parks levy.

A key catalyst for statewide use came in 2023 with passage of Oregon House Bill 3409, which charged Altenhoff’s office with creating funding for communities to enhance and track green infrastructure. ODF provides a basic version of TreePlotter free to cities under a federal grant. In Portland, Urban Forestry received support from the Portland Clean Energy Fund’s (PCEF’s) Equitable Tree Canopy program to customize the software for its own needs.

Complementing Urban Forestry’s Own Toolbox

TreePlotter has two components that aid this statewide greening effort. One is called TreePlotter Inventory; it’s what Portland’s Urban Forestry (UF) is using. The second one, TreePlotter Canopy, is a remote-sensing-based tool that uses aerial satellite photos to show canopy coverage. Together with other information, it produces a map-based means of applying multiple layers of information to help cities and towns determine geographically where the need for canopy is greatest based on factors including socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. This component also shows change in canopy over time.

Portland doesn’t use TreePlotter Canopy because UF staff have access to higher quality canopy cover data from Metro, says Jeff Ramsey. As well, UF is blessed with GIS-savvy staff who can combine that tool with other datasets including socioeconomic, urban heat, and canopy potential using UF’s own analysis (see Canopy Explorer). The public, tree advocates, or Portland City Councilors can use that public platform to track canopy citywide and within their own districts.

UF’s own expertise has generated actionable data; Portland’s tree canopy priority service areas map is one case in point. But it’s likely that some of Oregon’s smaller cities need something like TreePlotter Canopy because that is the best system they have access to, Ramsey says.

The Roll Out

“With the new system, Portland has moved to what is, in effect, a live tree inventory.”

Urban Forestry first introduced TreePlotter in 2024, a few years after the earlier Parks levy passed and resulted in hiring an operations team coordinator. The first UF group to start using it was Parks arborists, whose work had been mostly paper-based. The new tool, together with that new position, allowed UF to adopt preemptive parks maintenance for the first time. “Proactively maintaining parks is exactly what TreePlotter was built for,” says Ramsey.

Other UF programs are now using the new system, including staff who inspect Heritage Trees and those who handle pest and pathogen management.

All of UF’s tree planting programs were in GIS prior to UF’s adoption of TreePlotter, says Ramsey. Some data was in GIS and some in other systems, all unlinked. What was outside GIS was any information on tree maintenance or permitting. While permitting data remains outside TreePlotter (more on that below), maintenance data is stored there.

An Urban Forestry training of contractors; the screen reads “Planting Season Schedule 26.” Photo by Urban Forestry.

For example, UF’s new PCEF-funded, low-canopy-focused street tree planting program uses TreePlotter at every step. With it, staff communicate information about available sites and for what size tree. They collect property addresses for sending “opt-out” mailers to residents and track responses, record inspections updates, and assign pruning of newly planted trees at year three and five. Through this program, the City planted about 2,000 street trees in 2025, a portion of the nearly 7,000 planted or given away that year. As of fall 2025, all of UF’s various planting programs were using the new software.

The next step is to shift UF’s dozen or so contractors into it, which has already begun. The previous GIS systems UF had relied on were for internal use only and not accessible to contractors. Bringing them into TreePlotter will facilitate assigning them tree planting and maintenance work orders, and tracing the quantity and quality of work completed.

Eventually volunteers and other members of the public will also have access to the software. In fall 2024 UF staff dropped into TreePlotter the City’s latest street tree inventory data, on 252,000 trees. With the new system, Portland has moved to what is, in effect, a live tree inventory that includes, between periodic inventories, every new tree the City plants or removes, giving UF an up-to-the-minute count of trees. In the future Urban Forestry will likely steer the public to a site that contains the latest TreePlotter tree counts between inventories.

Seeking Better Reporting Capabilities

Inputting data into TreePlotter is easy, says Ramsey. Now UF is working with PlanIT Geo, the vendor, to figure out how to more easily pull summary data out of the system. Although UF commonly grabs data from TreePlotter to fulfill City Council requests and other reporting needs, says Ramsey, the system hasn’t yet replaced all of UF’s own program evaluation tools.

“Since we have the ability to create customized dashboards and web applications outside of TreePlotter, we will likely be building our own internal and external reporting tools over the next year,” he notes. One example of UF-generated public reporting is the street tree inventory dashboard.

Crossing Technologies

TreePlotter figures, in a small way, within the larger context of a recent City change that Trees for Life Oregon is monitoring.

We are concerned about the ramifications of moving Urban Forestry’s permitting and regulation team into Portland’s Permitting & Development Bureau, a shift that took place on October 1, 2025, after the City Council approved a budget amendment to do this. The transition of Urban Forestry’s Permitting and Regulation Workgroup into Portland Permitting & Development’s Tree Permitting Division will take time. TFLO will be monitoring the shift’s impacts across the board, including on staff time, which affects budgeting.

“At both the state and local levels, the data TreePlotter stores is invaluable for demonstrating to urban policymakers where and why investing in maintaining and expanding tree canopy matters.”

One technical factor that staff are working to manage is that TreePlotter is not compatible with AMANDA, the system that the Permitting & Development Bureau uses for its permitting data. For those interested in this technical issue, read on.

“TreePlotter and AMANDA can’t really talk to each other very well,” says UF’s Ramsey. A Permitting and Development Bureau tree inspector assessing a permit to remove a tree can’t go into TreePlotter and record that it has been approved or denied for removal, because the two systems can’t communicate at that level, he says. AMANDA is address-based, as are plumbing and electrical permits the public can access in PortlandMaps. TreePlotter is asset-based.

Says Chuck Barnes, a business analyst in P&D's Tree Permitting Division, “The future relationship between TreePlotter and AMANDA has not been fully defined. Though not natively compatible, records from one system may make reference to records in the other.”

For instance, the P&D Bureau (as well as 311) are using TreePlotter data to find information they need about trees that relate to their work in the field or to respond to emergencies. In such cases, these entities pull the relevant data from TreePlotter, including the tree’s ID, and enter it directly into their own system. It’s easier for P&D and 311 to have their AMANDA platform house this data so that they can see it and identify what information they need before, say, approving a permit or dispatching an emergency crew to a specific address.

Better Tracking Can Lead to Better Planning and Policies

From the broader, state perspective, in 2026 Oregon’s Urban & Community Forestry program, says Altenhoff, plans to “go big” to more actively promote TreePlotter’s adoption.

An Urban Forestry planting contractor recording and entering his work into TreePlotter. Photo by Urban Forestry.

His dream is to get at least 100 communities using this platform to measure trees and add them to the state database. Having most Oregon cities and towns using the same methodology on the same tree tracking platform will enable state urban forestry analysts to see trends and better plan ahead.

For instance, Oregon’s ash trees are starting to succumb to the ash-killing emerald ash borer, now present in at least five Oregon counties. Knowing where cities’ ash trees are and in what numbers would help officials plan in advance to identify funding to remove and replace their ashes, says Trees for Life Oregon’s Jim Gersbach, president of Oregon Community Trees.

A system like TreePlotter “will allow us to demonstrate the return on investment and what is being accomplished” as well as where more work is needed, says Altenhoff.

At both the state and local levels, the data TreePlotter stores is invaluable for demonstrating to urban policymakers where and why investing in maintaining and expanding tree canopy matters.

Tools like TreePlotter foreshadow the future, observes Altenhoff. AI technology may eventually replace volunteer-based tree inventories, he says, relegating to the past the act of humans hugging trees with a diameter tape measure.

If this is true, Trees for Life Oregon hopes it doesn’t happen soon. Getting volunteers in the field engaging in tree-related activities will always be a crucial way of getting the public to connect with urban trees and therefore want to preserve and protect them. At the same time, policy-focused tree advocates deeply appreciate the value of having better and more accurate data available to present to City leaders making decisions about our urban forest. Urban Forestry has already started preliminary work on Portland’s upcoming Title 11 tree code revision process. Whether revisiting the tree code will weaken or strengthen our urban tree canopy is unclear. But having a tool like TreePlotter to up our tree data game is certainly a positive.